I’m thinking incessantly about stories at the moment. Not, surprisingly, the old ones set in Russia, involving red shoes, golden rings, bears, witches and houses on chicken leg stilts. I’ve recently been returning to one type of story which had a huge influence on me whilst growing up, and still does – the cinematic, the film, and in some cases, the blockbuster. At the beginning of this year I decided to learn how stories are actually structured and formulated, and this led me unexpectedly into the world of screen-writing theory for TV and film, via John Yorke’s book, “Into The Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them.” By treating blockbuster films as common members of the same story world also inhabited by fairytales and ancient myths, I’ve delved into the fascinating set of patterns, shapes and codes which underpin them all.

Over Christmas, my family and I settled down to watch the latest Bond film, Skyfall, as I excitedly proclaimed that it was the best one yet. When it was over, my father announced that it was ‘bollocks’ – unbelievably slow-moving and boring – “the only good bit was the first ten minutes” (which featured a fight atop a speeding train, followed by Bond falling off a viaduct and seemingly plummeting to his death into the river below). My brother agreed that he had found the rest of the film a bit boring.

I found all of this amusing because for me, Skyfall was not only the most interesting Bond film I’d seen (I’ll be honest, I’ve never been that interested in them), but I felt that finally, after growing up with cocky, self-assured, lobster-faced (sorry Roger Moore) Bond’s japes in Moonraker, Live and Let Die, Octopussy, etc, Skyfall finally offered a glimpse into the man beneath the ‘Bond facade’.

The climax of Skyfall brings Bond back to Skyfall Estate in remote Scotland, where he grew up with his parents as a boy. The psychotic baddie is on his trail, and Bond and M are battening down the hatches, a sense of foreboding hanging in the air. Yes, the action virtually grinds to a halt at this point in the film, but something else is going on. Bond is back in the place where he lived as a boy, reunited with the estate’s wild-eyed gamekeeper, who knew him back then. Showing M around the castle, he points to the trapdoor leading down into the cellar, and says of Bond: “The night his parents died, he went down there and didn’t come out until the morning.”

Later that night, the psychotic villain and his barbaric helpers arrive with helicopters and machine guns, destroying Skyfall Estate until only a fireball remains. Bond survives by sheltering in that same cellar where he hid the night he learnt of the death of his parents. He eventually comes out alive, but his childhood home has been obliterated.  To me, this climax in the film has as much…harmony, symbolism and material worthy of Jungian analysis…as a Grimm’s fairytale. Circumstances have brought Bond back to the underground chasm of his unresolved grief. For a short little while, he drops the artifice of being ‘James Bond’ and faces up to the reality he’s turned his back on for so long – a childhood marred by grief. That night, as the enemy destroys the dusty, gloomy home of his childhood and he shelters in the cellar below, it feels as though James Bond cannot run any further from his past. The ‘enemy’ has cornered him, in the place he thought he had managed to evade. That night, symbolically, he faces that place – something is released. He comes out with nothing left, materially – only himself.

To me, this climax in the film has as much…harmony, symbolism and material worthy of Jungian analysis…as a Grimm’s fairytale. Circumstances have brought Bond back to the underground chasm of his unresolved grief. For a short little while, he drops the artifice of being ‘James Bond’ and faces up to the reality he’s turned his back on for so long – a childhood marred by grief. That night, as the enemy destroys the dusty, gloomy home of his childhood and he shelters in the cellar below, it feels as though James Bond cannot run any further from his past. The ‘enemy’ has cornered him, in the place he thought he had managed to evade. That night, symbolically, he faces that place – something is released. He comes out with nothing left, materially – only himself.

Whether you see it as a masterpiece worthy of endless Jungian analysis, or a particularly slow-moving Bond film, Skyfall highlights some key principles of story structure which I’m learning from Yorke’s book.

In his introduction, Yorke states that “dramatic structure is not a construct, but a product of human psychology, biology and physics.” The more I explore this structure underpinning story, the more clearly I understand what Yorke means. It’s a science. The pattern and shape of a story is no different from a mathematical equation, a chemical reaction. It’s a world of positive and negative, of opposing forces attempting to find harmony with each other. The only difference between science and storytelling is that in story, these little (+) and (-) symbols are veiled beneath characters.

Once upon a time, a character lacked something they desired, went on a journey to find that thing, and found it. A negatively-charged molecule goes on a journey to find the positive charge that it lacks: it’s a chemical equation. The greater the obstacles facing that molecule, the more satisfying the story, and through facing those obstacles, the molecule ends up changed: in a different chemical state. As Yorke says, “The essence of all drama is built on change, and the internal struggle a character must undergo in order to achieve it.”

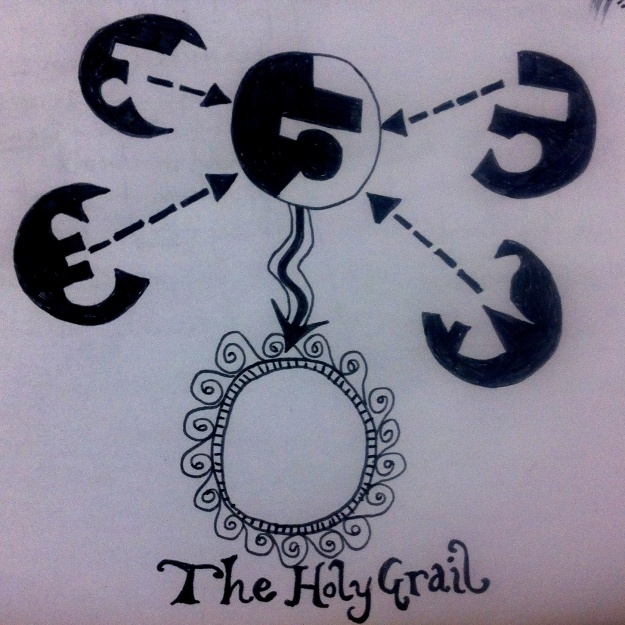

” a character goes in search of what they desire and lack – (they might have to look in many different places) – and in doing so they become complete.”

” a character goes in search of what they desire and lack – (they might have to look in many different places) – and in doing so they become complete.”

But Yorke’s book also puts its finger on the crucial reason why so many stories which follow this pattern do not deeply challenge or stir us. We consume these well-crafted stories and the messages within them, as in the case of the blockbuster film, but they wash over us and leave us gently entertained, but rather indifferent. Yorke points out that although all stories somehow involve a character with a desire, and track their journey to fulfil this desire, the stories which really affect us involve a character whose desire is in conflict with their need.

Many stories, from fairytales to blockbusters, involve a character’s successful search for a particular thing, concept or outcome – wealth, popularity, strength, a ring, a grail… Yes, these characters often undergo inner changes in order to find this thing, teaching us about sacrifice, bravery, perseverance, etc. etc. – but they are what Yorke calls two dimensional stories. What happens when a character starts off searching for something, and in the process of reaching it, realises that they were searching for the wrong thing in the first place? This…is meaty. This is a three dimensional story which gives us a glimpse of what we really thirst for in a story – a character dealing with inner conflict.

In a three dimensional story (which Yorke describes as a sort of wholesome, multi-grain, sourdough rye bread compared with the ubiquitous, white supermarket loaf of the two dimensional story) a character starts off with a set of ‘superficial wants’, but during the course of the story these are “…rejected in favour of the more profound unconscious hunger inside.” These stories speak of the ultimate challenge we face as human beings – the ability to separate the things which we think we need or want from those things which we actually need – by that, I suppose, I mean things which bring us true inner fulfillment. But what is inner fulfillment anyway? What does it even look or feel like, and how many of us humans are midway through misled quests, some set to last decades, perhaps lifetimes?

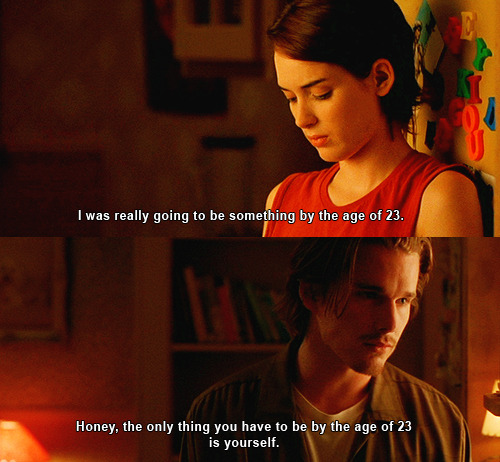

A film which I watched so many times throughout my early teens that it seemed to form a comforting wallpaper backdrop to that chapter of my life is Reality Bites (1994), a kind of Generation X indie hit written by Helen Childress and starring the beautiful, youthful Winona Ryder and Ethan Hawke. Re-watching it now, I understand why I needed that film – and its story – so badly while I was growing up. It’s a perfect example of three-dimensional storytelling.

Lelaina (Ryder) has just graduated from university with a media degree and wants to make a difference to the world by becoming a documentary film maker. She works on her own documentary films in her spare time, whilst earning a living as a runner for an awful, soul-destroying TV chat show. She meets Michael – a nice, really nice, yuppie TV producer who falls for her and wants to help her fulfil her dream by getting her documentary onto a mainstream MTV show. Then there’s Troy (Hawke), a greasy-haired, unemployed slacker and musician – highly intelligent, unfulfilled in life but acutely aware of the games people play to climb their way to supposed ‘success’ – and he doesn’t want any of it.

Who should Lelaina choose – good, kind-hearted Michael, who has the potential to help her reach her ultimate goal in life, or bitter, jaded Troy, whose opinions hurt and offend Lelaina, yet seem to hold an inescapable power over her? Every ounce of good sense dictates to the viewer that she should choose Michael, the good guy, whose genuine interest it is to bring Lelaina fulfillment. And yet – some irrational impulse within you urges her to choose cynical, messed up Troy – who cannot promise her anything, who is riddled with fear and self-loathing.

Why? At last I think I understand why. Because although Michael offers Lelaina the thing that she most wishes for, it is not the thing that she really needs. Lelaina has been chasing the wrong dream. To successfully ‘break through’ in the world that she’s hungering after would involve compromising herself – but she couldn’t know that until she arrived there, and by then it would be too late. Troy doesn’t offer Lelaina the path to her dreams – he offers her the chance to see that what she was chasing after was a false dream that would have forced her to become someone she was not. By pointing out that what she is thirsting after is a load of bullshit, Troy is actually offering Lelaina a gift far greater than Michael’s promise of success on an MTV show.  Stories like these were vital to me during my adolescence. Without realising it, they showed me that so many of the goals being presented to me were misleading ones, and inspired me to begin to make choices which would lead me towards the goals I truly wanted, not goals that I, or other people, thought I ought to have.

Stories like these were vital to me during my adolescence. Without realising it, they showed me that so many of the goals being presented to me were misleading ones, and inspired me to begin to make choices which would lead me towards the goals I truly wanted, not goals that I, or other people, thought I ought to have.

So much is said about the importance and need for stories today, but learning about how they are structured and how they work has been a real epiphany for me. This is a science – a harmonious world unto itself, governed by its own set of laws and forces. And somehow, by understanding the laws inherent in story, perhaps we begin to see those very same laws at work in our real lives? If we can analyse stories to clearly see the inner predicament facing a character, surely we can use that very same analysing method to make sense of our own lives?

Maybe a fluency in this ‘story-crafting’ language is a long-overlooked, key component of human emotional intelligence? Perhaps it is indisputably treated as such in the cultures where stories are, to this day, known to contain tools for healing physical and emotional ills? (as spoken of in this lovely blogpost by mythopoetic writer and artist Terri Windling) Perhaps story intelligence is another, as-yet unacknowledged approach to learning within Howard Gardner’s concept of Multiple Intelligences? People are certainly beginning to gather for serious discussions on how we can use story to address the environmental, ecological and spiritual problems of our time – the Findhorn Foundation’s New Story Summit was one such recent experiment.

Although I continue to hungrily absorb these insights in story theory from the screen-writing world, from which the blockbusters of tomorrow will be born, I will be bringing them back into my own domain, which probably has a lot more in common with Baba Yaga than it does with James Bond. But delving into the world of the blockbuster film has taught me more about story than I could have ever imagined, and I’ve only scratched the surface.

Baba Yaga illustration by Rima Staines

Baba Yaga illustration by Rima Staines