This year began with a stint of freelance work as a research assistant for a project bringing together various key figures from British puppetry to ask what puppetry, and the professionals specialising in it, truly needs to thrive in England. Having sifted through several hundred surveys completed by such professionals, one particular need came across strongly – that of puppetry not just being seen as an artform for children. This need was echoed by members of the Little Angel Theatre in London, whose Jabberwocky, a marionette-based interpretation of Lewis Carroll’s poem, was doing very well but not attracting quite as many adult viewers as the theatre had hoped. I saw Jabberwocky and found it dark, hypnotic and visually-mesmerising, with a sultry, electronica-tinged soundscape by multi-media artist Hannah Marshall. It was absolutely suitable for an adult audience – so why did it struggle to attract one?

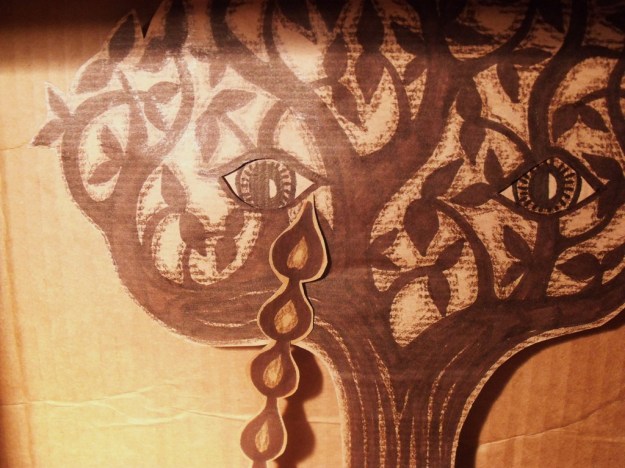

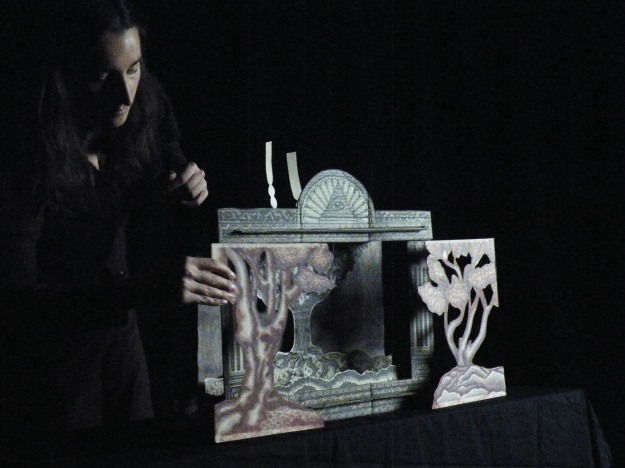

Running in parallel to this problem highlighted to me during my puppetry research work, was another, personal one – my show, The Weeping Tree. A six year old ongoing, incomplete project – a toy theatre comprising cardboard panels, wire hooks and a paper tree with hand-animated, paper teardrops streaming from its eyes. The Weeping Tree began in 2009, with a doodle on brown parcel paper in the small, blacked-out puppetry studio at at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama where I was studying at the time. I drew a tree, it had eyes, and the tree wept. That was all I knew. An illustration drawn in an idle moment led to the creation of my first ever toy theatre.  I had been obsessed by toy theatres for some time – this beautiful Victorian family entertainment tradition based on two dimensional panels of illustrated scenery and characters, hand-animated within a miniature proscenium arch theatre (see London’s Pollocks Toy Museum). Inspired by a story taking shape in my head, and a book of medieval woodcuts, I began making my toy theatre. I had no design, and no knowledge of how to make one – it was a truly cobbled together creation comprising endless fiddly, interconnecting cardboard pieces. It’s a wonder it stood up at all. Terry Gilliam would have been proud.

I had been obsessed by toy theatres for some time – this beautiful Victorian family entertainment tradition based on two dimensional panels of illustrated scenery and characters, hand-animated within a miniature proscenium arch theatre (see London’s Pollocks Toy Museum). Inspired by a story taking shape in my head, and a book of medieval woodcuts, I began making my toy theatre. I had no design, and no knowledge of how to make one – it was a truly cobbled together creation comprising endless fiddly, interconnecting cardboard pieces. It’s a wonder it stood up at all. Terry Gilliam would have been proud. The following year, I applied to perform The Weeping Tree at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama’s International Student Puppet Festival. I was determined for it to be a completely non-verbal performance (more on that later) – for the visuals to tell the story. Accompanied by a pre-recorded medieval soundtrack on a CD, the thirty minute, non-verbal show was performed to a reasonably-sized audience. As soon as it came to an end, I knew that it hadn’t worked. This was confirmed when I asked a colleague what they thought of the show and they sighed, then said “You know….you have such a good voice, why don’t you narrate it?” The non-verbal, visual and emotive journey I had hoped for had seriously lacked something – and the helpful advice to give it words, those very things I was trying to avoid, was a further blow.

The following year, I applied to perform The Weeping Tree at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama’s International Student Puppet Festival. I was determined for it to be a completely non-verbal performance (more on that later) – for the visuals to tell the story. Accompanied by a pre-recorded medieval soundtrack on a CD, the thirty minute, non-verbal show was performed to a reasonably-sized audience. As soon as it came to an end, I knew that it hadn’t worked. This was confirmed when I asked a colleague what they thought of the show and they sighed, then said “You know….you have such a good voice, why don’t you narrate it?” The non-verbal, visual and emotive journey I had hoped for had seriously lacked something – and the helpful advice to give it words, those very things I was trying to avoid, was a further blow.

That summer, the fiddly interconnecting cardboard sections were dismantled and The Weeping Tree was flat-packed into a suitcase, to accompany me on an internship to Great Small Works’ International Toy Theater Festival in Brooklyn, New York. As I had hoped, it was an explosion of inspiring, unusual and quirky small scale theatre based around the toy theatre tradition – it was also an opportunity to give The Weeping Tree another shot at performing. This time, the set-up dictated a different performing style – I would be performing ‘on repeat’ to an ambulatory, transient audience wandering around the festival’s Toy Theater Museum. The performance needed to last five to ten minutes, and be appealing to a milling, wandering crowd.

Inspired by the playful, brash style of many of my US performer counterparts, I let go of my deadly serious, holier than thou performing attitude, and condensed the show to a slightly farcical five minutes, with some choice words and a catchy melody thrown in. This time, I could immediately see my audiences’ appreciation and enjoyment – it worked. This more successful ‘sequel’ gave me hope that there was life, yet, in The Weeping Tree, if I was open to reinvention – but I had used words – wasn’t the whole point to not use words…?

Back in England, I set to work developing my show visually, using some of the inspiring ‘folk’ visual storytelling techniques I’d been exposed to at the Great Small Works festival. I realised that if I really did want images to tell this story, rather than words, I would need to expand my show’s visual ‘landscape’. I began by creating a moving panorama box (see below), a scrolling automata device showing a moving picture sequence. This allowed me to show the central outward, and homeward journey taken by the protagonist of the story. Next, I introduced a set of Kamishibai cards – illustrated story cards based on the Japanese tradition which later evolved into anime. These allowed me to map out detailed aspects of important parts of the storyline.

Next, I introduced a set of Kamishibai cards – illustrated story cards based on the Japanese tradition which later evolved into anime. These allowed me to map out detailed aspects of important parts of the storyline.  With The Weeping Tree now more visually developed, I performed it a few more times in low key settings, teaming up with a fellow performer so that I could focus on creating live music and singing, whilst he narrated and animated. Yes, a richer visual landscape and new elements of music and song were beginning to bring the piece alive – but the story still relied on the spoken word…and at that point, life took over and The Weeping Tree was placed on a shelf beneath a cloth, where it remained for over a year.

With The Weeping Tree now more visually developed, I performed it a few more times in low key settings, teaming up with a fellow performer so that I could focus on creating live music and singing, whilst he narrated and animated. Yes, a richer visual landscape and new elements of music and song were beginning to bring the piece alive – but the story still relied on the spoken word…and at that point, life took over and The Weeping Tree was placed on a shelf beneath a cloth, where it remained for over a year. But during the year that The Weeping Tree sat there on its shelf, gathering dust, I chanced upon a series of unexpected and truly inspiring theatrical experiences which stayed at the back of my mind, begging to be written about and properly reflected on. I didn’t realise it at the time, but these individual inspirations came together to create a vision – a vision of the kind of work I’d like to make, a vision of what The Weeping Tree might be able to become, and also, a vision of how performance in general can transcend the kinds of barriers which dictate that, for example, puppetry is ‘just for children’.

But during the year that The Weeping Tree sat there on its shelf, gathering dust, I chanced upon a series of unexpected and truly inspiring theatrical experiences which stayed at the back of my mind, begging to be written about and properly reflected on. I didn’t realise it at the time, but these individual inspirations came together to create a vision – a vision of the kind of work I’d like to make, a vision of what The Weeping Tree might be able to become, and also, a vision of how performance in general can transcend the kinds of barriers which dictate that, for example, puppetry is ‘just for children’.

Inspiration #1: two uncategorisable gigs

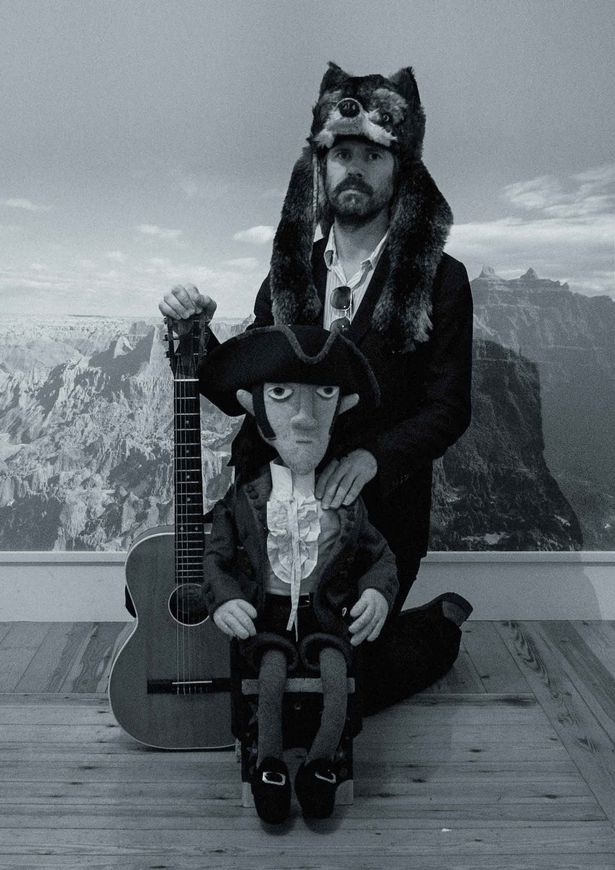

At a festival last summer, I watched Gruff Rhys, Welsh former frontman of the Super Furry Animals, perform his solo concept album American Interior. I had come to his show not only because I liked the songs, but also because I had heard that this was not going to be any ‘normal’ gig – and these rumours proved correct. The musician settled himself on stage, next to a felt puppet dressed in 1800’s style, and began to tell a story. He reccounted the biographical tale of John Evans, a Welshman who left his small village in the 1800’s to journey to North America in search of a fabled, near mythical welsh-speaking tribe of Native Americans (he never did find it). Rhys’s songs wove through the story – told endearingly and humorously in a dead-pan, thick welsh accent, as did Powerpoint slides showing ‘puppet’ John Evans’s modernday roadtrip pilgrimage across the USA, joining Rhys to follow in the original John Evans’s footsteps. The gig left a huge imprint on me because it showed how utterly refreshing it is to play around with disciplines. Framed by the experience of a ‘gig’, this was a combination of oral storytelling, puppetry, film and live music. It felt raw and totally engaging for those thousand-or-so people squeezed together in the darkness, listening intently to Rhys’s story, laughing at the off-beat humour and immersing themselves in his songs. The gig also reminded me of the immediacy, and power, of music as a driving, central force in a performance – how potent to combine this emotional intensity with a story, a theatre performance!

The gig left a huge imprint on me because it showed how utterly refreshing it is to play around with disciplines. Framed by the experience of a ‘gig’, this was a combination of oral storytelling, puppetry, film and live music. It felt raw and totally engaging for those thousand-or-so people squeezed together in the darkness, listening intently to Rhys’s story, laughing at the off-beat humour and immersing themselves in his songs. The gig also reminded me of the immediacy, and power, of music as a driving, central force in a performance – how potent to combine this emotional intensity with a story, a theatre performance!

The originality of Rhys’s ‘audio-visual storytelling’ gig’ was rivalled only by another gig I witnessed that year – that of enigmatic swedish ‘psych’ band Goat. Goat also used the framework of a gig to create a totally unique, multi-disciplinary theatrical experience. Entering the stage heavily cloaked in extravagant folk costumes and masks, the group fused their songs with ceremonial dance choreography, echoing sacred ritual traditions from Asia to Northern Scandanavia. Using music as their glue, the group joined together an eclectic bundle of inspirations, defying categorization. Once again, it seemed to be proof that the heart and soul of performance lies in the places where artforms overlap and lose their clear distinctions.  Inspiration #2: a theatre company that never uses words

Inspiration #2: a theatre company that never uses words

For a while, I had put my ideas about creating completely non-verbal performance to one side – until I stumbled upon the website of a company which stirred those impulses once more. Mimika Theatre is a artist couple based in the north of England who create visual theatre shows, for children, which are always non-verbal. Gazing at the company’s website showed me that Mimika had an aim echoing my own, and that they were successfully fulfilling it. Within a self-contained white, domed tent they fused exquisite, hand-crafted visual landscapes and puppetry with music and lighting, creating an immersive experience which seemed to provoke just as much awe, wonder and genuine emotion in adult onlookers as in their child-based audiences. “Spells are woven silently…This is true transformation, the imagination is set free.” The Scotsman.

Reading about Mimika’s creative aims and seeing the rapturous reviews of their shows (as pointed out by the company, such reviews regularly feature the word ‘magical’) inspired me to believe once again in the power of the non-verbal, the purely visual. This company understood what I had been getting at all along (but not quite succeeding with) – that a completely non-verbal immersion into visual imagery and music allows the space to interpret, explore, imagine, and undertake a profound ‘inner’ journey. Although Mimika’s shows were aimed specifically towards children, they were breaking other barriers, besides those of age – they could be engaged with by children regardless of language ability, and those with special needs. Althought Mimika were working within the domain of children’s theatre, they seemed to be creating something universal.

Inspiration #3: a ritual theatre reinvention

The third inspiring encounter took place in the cosy little Pit theatre space of London’s Barbican Theatre, in January. I had travelled far to come and witness New York puppetry artist Basil Twist’s Dogugaeshi, a visual theatre piece based on the rare Japanese folk theatre tradition of the same name. The show began with a veiled, rectangular proscenium arch ‘portal’ opening to reveal layer after layer of hand-painted and illustrated panels, each disappearing to reveal the next and the next, taking the eye on a journey into the unknown. During the hour-long performance the panels slid, spun, closed and opened, creating a dizzyingly fast-paced visual spectacle, ever leading towards that final, distant panel depicting the snowy peak of Mount Fugi. A performance based, in essence, on opening and shutting doors – but somehow suggesting a sacred journey towards a distant, elusive goal. This animated journey was woven together by the music of a traditional shamisen player, and the appearance, at intervals, of a mysterious, long-haired dragon puppet dancing across the set.

The inspiration Dogugaeshi contained for me was a recognition of the power of ritual. By working with these traditional elements of dogugaeshi performance, namely the dozens of layers of sliding animated panels, the shamisen music and the dancing dragon, Basil Twist was able to create a unique fusion via a set of ritual tools. The performance was based on a simple collection of elements – but the ritualistic structure held these elements together, and allowed them to be engaged with in a direct and unadulterated way. Again, this was an example of a performance that broke through barriers and represented accessibility – through being based on a simple framework of rituals, a raw, broken down experience had been created which could have just as easily been enjoyed by a child, as an adult. And again, this accessibility had much to do with the fact that words had not been used, nor needed.

So what do these bundles of inspiration have to offer me as I prepare to take the dusty cloth off The Weeping Tree and enter into its story, once again? They tell me to choose my raw, simple elements – the visual, and music – and to treat them as such, keeping them unadorned, so as to be appreciated in their fullest capacity. These inspirations tell me to think beyond the box – which is theatre as we know it – and to think, instead, in terms of Peter Brook’s Empty Space, a place where a circle can be drawn in the sand to mark a space of liminal possibility. These inspirations tell me that ritual is the glue that has been used since the first circle was drawn in the sand, to combine endlessly diverse elements into a performance. And finally, these inspirations show me that, when all of the above are in place, a performance doesn’t need words.

At some point in history (our Western European history, at least), puppets began to be used predominantly to tell stories for children. Over time, the ancient glue of ritual holding these performances together was added to with other subtle, aesthetic and cultural baggage – baggage which now pigeon-holes puppetry into being something it is not, and distracts from its true nature. The inspirations I’ve spoken of can show not only me, but other creators of puppetry, how to shake off its residual cultural associations, re-invent it, and restore it to the ageless, ancient performance tool that it is.